HOWARD HICKSON'S

HISTORIES

[Index]

Men in Blue

Fort Halleck, Nevada (1867-1886)

In 1867 Central

Pacific Railroad construction crews were laying rails toward tracks of

the Union Pacific to complete the first transcontinental railroad in the

United States. Back east in Washington, D.C. army brass decided to build

a fort to protect the workers from Indian attacks. It didn't matter that

there had been no battles in northern Nevada in recent years.

Captain S.P. Smith, formerly of Fort Ruby,

was at Winnemucca Ridge when he received orders to found Camp Halleck.

With Lieutenant Augustus Starr (now you know where Starr Valley got its

name) he led Company H, Eighth Cavalry to Cottonwood Creek a few miles

south of Secret Pass.

Once there, Capt. Smith bought property for the

fort (fort or camp, it changed status from time to time, I will use fort

for the sake of continuity) from First Lieutenant William G. Seamonds.

Seamonds had been stationed at Fort Ruby but was retired and had the honor

of being the first settler in what would be Halleck Valley. The post was

named in honor of General Henry W. Halleck (right), Commander-in-Chief

of the US Army in 1867. The new military reservation covered 17 square

miles of grazing areas, forests for wood, and the post proper.

Smith put his soldiers to work constructing

dugouts for the enlisted people and putting up tents for the officers.

Smith was a tough Indian fighter from the Overland War of 1863. He was

also an oppressive leader, always insisting that his men follow military

rules to the letter. If not, they were flogged. One of his reports noted

that of a roster of 70, 15 soldiers, not wanting to face the whip, had

deserted.

Shoshones and Paiutes visited the fledgling

fort to watch the men work. The soldiers, in turn, sometimes traveled to

nearby Indian camps to watch dances. There wasn't any danger from the peaceful

local natives. Occasionally a wagon train detoured from the Humboldt River

to the fort but they too were in no danger.

Food was freighted to the fort from Austin.

The choice didn't vary. There was flour, beef, bacon, beans, coffee, tea,

rice, and sugar - the only delicacy was dried apples. If the men wanted

some variation they patronized a nearby store where they bought eggs at

$2 a dozen, butter for $2.50 a pound, and canned goods were $1 each. Double

that price because the army was paid in greenbacks not accepted by local

merchants who converted them to gold for a 50% commission.

Water was frequently a problem. Cottonwood

Creek dried up part of the year so a ditch was dug from another stream

to the west. Additionally, barrels were filled from a nearby spring and

brought to the camp by wagon. When there was enough water the men planted

gardens in self defense to provide some variation in their diet.

By December, 1868 there were two companies

at Fort Halleck: Company D, Eighth Cavalry, with two officers and 50 enlisted

men and Company H, Eighth Cavalry, with two officers and 64 soldiers. Add

to those one assistant surgeon, one hospital steward, one hospital matron,

and three laundresses. If the math is right, that's 120 people.

More permanent structures were built of cottonwood

logs and adobe. Officers, of course, were assigned to the adobes. They

were more weatherproof.

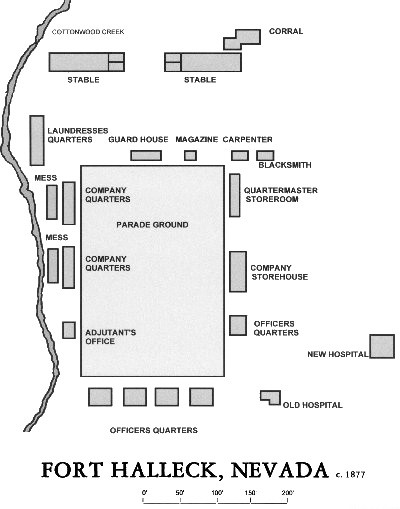

Fort Halleck about 1878 - Photo

from Northeastern Nevada Museum, Elko.

In 1869 the Central Pacific was completed and

supplies came by railroad, off loading at Halleck Station, about twelve

miles to the north.

By the 1870s, local farmers and ranchers depended

on the fort for entertainment and economic strength. Many soldiers, especially

on payday, took their business to nearby John Day Ranch where there was

a saloon, dance hall, and a stock of professional girls with loose morals.

Drawing by the author.

Attempts were made to bring a little civilization

to the place by wives of men stationed at Fort Halleck. They tried to bring

some semblance of civilization by promoting religious and social

activities. The commanding officer's sister tried converting local Indians

to Christianity. It didn't work out. The services were well attended but

the Indians didn't understand English. They came for the music and refreshments..

Since there was no danger from the Indians,

commanding officers from time to time wrote letters to their headquarters

suggesting closure of the fort. Those efforts were always met with much

resistance from local settlers because their livelihoods were threatened

by the inevitable end had to come someday.

Soldiers from Fort Halleck never fought any

local battles but they still saw plenty of action: 131 men, under the command

of Lt. George R. Bacon, fought in the Modoc War in 1873; 1877 saw troops

from the fort fighting the Nez Perce in Idaho; and, in 1885, they were

involved in the Apache War in Arizona.

Major General O.O. Howard wrote the letter

that started the fort's demise: "There seems to be no good reason why Fort

Halleck, Nevada should not be abandoned. It is 12 miles from the railroad

and possesses no paramount importance as a strategic point. The settlers

are interested in some degree in keeping the Post, in order to have a market

near at hand for grain and other supplies they can raise. It is, considering

its size, the most expensive Post in the Department."

In1886, the Secretary of War finally authorized

abandonment of the military reserve and turning the property over to the

Department of the Interior.

After the soldiers left local settlers moved

in and cannibalized lumber, roofing material, and whatever else they could

use. It is probably there are still ranches with parts of Fort Halleck

in their buildings. It didn't take long for the place to fall into disrepair

and for nature to reclaim the land..

Daughters of Utah Pioneers erected a monument

in 1939 noting the fort's 19 years of service. It is on the south side

of the road. About all that remains today are mounds marking foundations

and cottonwood trees that once bordered the parade ground. Perhaps, with

the right circumstances and frame of mind, a visitor might hear cadence

being called, horses neighing, firearms practice, construction sounds,

and maybe a soldier in quarters playing his harmonica and thinking of the

girl he left behind. Walk a few moments in the past.

Howard Hickson

September 8, 2002

Source: Most of the information in this vignette came

from Halleck Country - The Story of the Land and its People by Edna

B. Patterson and Louise A. Beebe published in 1982.

©Copyright 2002 by Howard Hickson.

[Back to Hickson's

Histories Index]

|