Rest in Peace – Maybe Hundreds of people traveling by wagon train to a new home and promising dreams on the other side of the Sierra Nevada died on the California Trail. The journey was hard on body and soul. Historians say the route averaged a grave every 500 feet.

Lucinda Parker Duncan died of a heart attack at Gravelly Ford on the Humboldt River near Beowawe, Nevada. Matriarch of a wagon train composed mostly of her family members. Lucinda always rode in a carriage at the front. By necessity, she was buried next to the trail and her family continued on west.

When the last CPRR tracks were laid in mid-1869 at Promontory, Utah Territory, thousands of Chinese workers were laid off. Many of them stayed in the new railroad communities while others moved to mining camps. Tuscarora had the largest Chinese settlement between the Mississippi River and San Francisco.

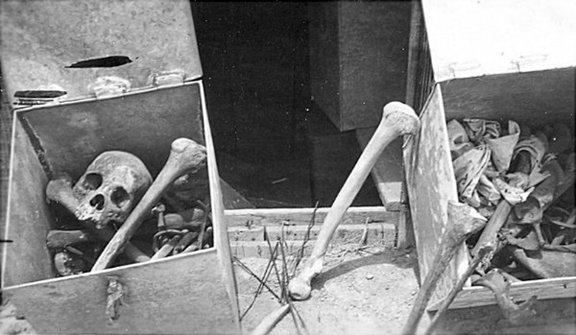

When a Chinese died, the body was buried with traditional funereal ceremony. It was sometimes a temporary interment. Most of those who had come from China to work in the United States wanted to return. When possible, and money was available, the journey back to China began.

The deceased’s bones were exhumed and placed on a cloth. Any remaining organic matter was removed with a stiff wire brush. It was forbidden to use a knife to clean the bones. A fresh cloth was used to wipe the bones after brushing, then were cleaned a third time using another clean cloth. The disinfected bones were then placed in a zinc box, hermetically sealed, and shipped to China. When the remains arrived by ship, relatives placed them in jars and performed elaborate burial services. Pioneer, Nevada, a gold mining in southern Nevada, boomed less than a year. That was long enough to blossom into a full fledged town of 2,500 people with dreams of becoming rich. From the fall of 1904 when the first claim was staked out to the big year of production ending in 1909 the place slowly sputtered to life then boomed for less than eleven months. Pioneer’s first death came on March 23, 1909. Fred Pollens died in the Central Hotel from a common ailment in those days – he drank himself into oblivion. In most mining camps, the population usually took on the responsibility of burying one of its own. A casket came from Rhyolite and a hole dug about a mile up Springdale road. One of the mourners picked up a few exposed rocks at the grave site. After crushing one of them, he panned this stuff and found specks of gold. Poor Pollens was, of course, unearthed and taken up Springdale road. A stick of dynamite opened a new hole for the deceased. The corpse wasn’t buried there either because the blast exposed a promising ledge containing gold. Pioneer citizens gave up and shipped Fred Pollens to Goldfield where he had once lived. Hopefully, he found a final resting place there.

Sometimes, in the American West, a final resting place wasn’t necessarily final.

Sources: “The Wagon Train of Lucinda Duncan – 1863,” Carolyn L. Stewart, Northeastern Nevada Historical Society Quarterly, 99-1; Hearing: H.R. 272, Eureka County, Nevada Land Conveyance, Subcommittee on National Parks, Recreation and Public Lands, April 8, 2003; Pacific Tourist, 1879; Pioneer Nevada, Volume Two, Harold’s Club, Reno, Nevada, 1966; Nevada’s Northeast Frontier, Edna Patterson, Louise Ulph (now Beebe), and Victor Goodwin, reprint by Northeastern Nevada Historical Society, Elko, 1991; Dale Porter, Elko; 2009 Nevada Historic Mining Calendar, published by the Society of Mining Metallurgy and Exploration, Inc., written by Phillip E. Earl. Photos from the Northeastern Nevada Museum, Elko, archives. . ©Copyright 2009 by Howard Hickson |

Lucinda died August 15, 1863. Five years later, Workers of the Central Pacific Railroad discovered her crude grave where tracks were scheduled to be laid. They dug up her remains and moved them to a hill just south. Over the years it was called the “Maiden’s Grave” even after her age was discovered. Born in Virginia about 1793, she was around seventy years old, a ripe old age in those times. Still, it was a romantic thought. Her final resting place, now a small cemetery with several other plots, is well maintained. Railroad crews of the Central Pacific, Southern Pacific, and Union Pacific railroads kept the place up for decades until the cemetery was deeded in 2003 to Eureka County by the BLM.

Lucinda died August 15, 1863. Five years later, Workers of the Central Pacific Railroad discovered her crude grave where tracks were scheduled to be laid. They dug up her remains and moved them to a hill just south. Over the years it was called the “Maiden’s Grave” even after her age was discovered. Born in Virginia about 1793, she was around seventy years old, a ripe old age in those times. Still, it was a romantic thought. Her final resting place, now a small cemetery with several other plots, is well maintained. Railroad crews of the Central Pacific, Southern Pacific, and Union Pacific railroads kept the place up for decades until the cemetery was deeded in 2003 to Eureka County by the BLM.

Fort Halleck soldiers who died there were buried in the post’s cemetery. After the place was closed, their remains were exhumed and taken to the San Francisco National Cemetery where, in sight of the Golden Gate Bridge, they now rest in peace.

Fort Halleck soldiers who died there were buried in the post’s cemetery. After the place was closed, their remains were exhumed and taken to the San Francisco National Cemetery where, in sight of the Golden Gate Bridge, they now rest in peace.